There I was peeing in my corduroys and pleading with God to not let me die!

I was hiding behind the pine boughs at the corner of our house choking on a solid snowball that was lodged in the back of my throat, frantically digging the ice out with my little frozen fingers. It was brutal. Maybe my warm salty tears helped me survive, or pure determination to not die on a perfect winter’s night, but all of it, the hiding, the digging, the tears, the panic, the silence, and the prayers to God from a scared little girl under a tree, changed the course of my life.

I lived to tell the tale.

I was ridiculously excited earlier that evening. It was snowing hard like a dramatic scene in a movie, and my innocent romantic self believed this was the most beautiful family moment ever, and if memory serves, it was.

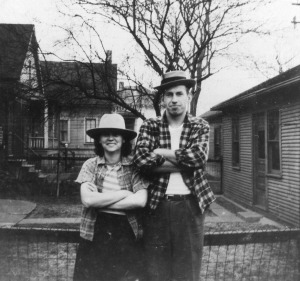

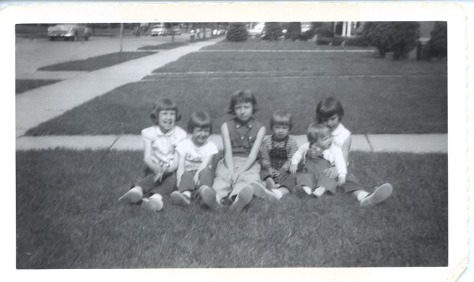

My mother had been anxiously waiting for my father to get home from his coaching job in Detroit. It was a long commute out to Roseville, a classic 1950s suburb made for making babies and building the future. The drive was made longer by blizzard conditions. There would be no calling, no texting or tracking, no weather reports at hand, or maps of road closures or accidents marked on Google maps; it was the mid-1960s. People just waited and prayed, paced, or ranted, depending on the night. Dinner had already been served to this family of almost all girls, six of us and one little boy, so the dishes were done, and the kitchen cleaned up and “closed” as my mom used to proclaim. It was all just a waiting game now, a candle lit in the window, and us littlest ones with our chins on the sill, watching for his car through the sparkly swirls of frosted windowpanes.

At last the lights of our station wagon, two hazy beams at the end of a tunnel, could be seen slowly creeping down tire trenches in the middle of our snow-covered street, tracks made only by the grace of some other dad cutting the path before him. By the time my father walked in the door, the top of his head seemingly just clearing the door frame, he was tired and spent. His shoulders sagging with the heaviness of his wet woolen overcoat, his tweed hat holding volumes of snow above his brow, rubber boots buckled over his ‘street shoes,’ and huge leather gloves that smelled of tobacco and coffee, like the familiar aroma of dad’s car, he was told, “Don’t even come in!”

He needed to shovel the sidewalk so the mailman wouldn’t fall in the morning, and he could take some of the girls to help. He was to do the driveway in the morning so the milkman could make his way up from the street to our milk shoot without slipping while carrying his usual load of six gallons of milk, all in half-gallon glass bottles. Customer service was a two-way street in our world.

Upon this command, there was this uncertain energy in the vestibule. We were all standing there at the door waiting to greet him, but who would be going back out? I knew who could shovel, and it wasn’t me. I was barely seven or eight, but oh my goodness, how I wanted to go outside with the rest of them! There was no begging. That was a surefire way to get nothing, but mom yielded quickly. We could all go out, but we had to stay on the sidewalk so we didn’t mess up the pristine layer of glistening snow on her lawn.

Ecstatic, we were all running around digging in closets and sleeves for hats and scarfs and lost mittens. Busy hands were zipping and buttoning-up the little ones. I was so full of joy, I could hardly think. The privilege of helping dad shovel was left to the older girls, though I’m not sure any of them thought it was a special deal. I was sent with my other siblings carefully muffled and mittened, capped and booted, into the snowy night to ‘help’ as big clumps of heavy snow made their way down onto the slanted rooftops of the identical two-story, mid-century modest homes of our quiet neighborhood.

After the giddy rush of anxious sisters got out the door, we stood in the hush of a late-night snow which by this point had left a couple feet for my father’s arms to heave-up and move. Soon my dad and sisters were shoveling away, we were catching snowflakes on our tongues, rules were being barked to stay off the lawn, and someone (probably my dad) threw a snowball. And so it started.

We were a family of 10, though when I was that young, we were only nine altogether. Our front lawn was our badminton court, our hockey and football field, the place where Red Rover, Red Rover was called over! The ‘side-drive’ was for handball and basketball, and the street was for baseball, kickball, and reserved for playing ‘catch.’ We didn’t need the rest of the neighborhood kids to have a game of anything, except they needed us. My dad was probably the one dad on our block that would hang out with all of us, run the bases, show kids how to handle a basketball, swing a bat, align one’s undisciplined fingers with the laces on the football, and he was actually qualified and patient. Some of those kids showed up for the snowball fight as if they were waiting at their windows for all of us to come out! Nothing was planned, as was the general course of things in those days. It just happened. With that first throw, a huge snowball fight erupted.

I was so excited just to be included, to be involved, to be a part of my great family of which I was in love. Balls were flying and hitting in every direction. Visibility was null. I was knocked over by some of those snow torpedoes a few times. My older sisters, now in high school and junior high, were athletes, so there was little timidity. I knew I had to be courageous if I wanted to stay in the game. I can’t even remember how many I threw, attempts that probably didn’t get far, maybe hitting a boot or the bottom of a coat.

At one point I was bent over laughing hysterically with my sister Clara. We couldn’t believe all this was happening! We were out there with the big kids in the middle of the night having fun! I strategically packed a snowball with the wet wind and snow pelting my face, my butt in the air and my back to the action. I was getting the hang of it. I came up, turned with my arm in a throwing position, mouth wide open in a war cry and BAM!

I was hit hard by a deadly snowball right into my wide-open mouth! Don’t laugh! I was just a skinny little girl! The sound was deafening, like life suddenly came to a violent halt! All I could hear was the muffled sound of gray shadowy figures now moving in slow motion. There was no time to feel humiliated, but I did. I couldn’t swallow. I thought I couldn’t breathe, and I definitely couldn’t speak. In the fighting frenzy, I couldn’t see my dad, and no one understood my waving arms. I couldn’t even move my jaw. I was choking on a huge ice ball, painstakingly trudging with little success through the knee-deep snow, falling and struggling to get anywhere, but no one seemed to see me.

I crawled to our pine tree at the corner of our house, under which I spent my summers playing Barbie and hiding during neighbor games like ‘Bloody Murder’ and “Hotsy Totsy.” Digging with my bare fingers in a silent hysteria, gasping for air and gagging on melting snow, my mouth dripping with saliva and snot and blood; nothing moved. The harder I tried to get that snowball out of my mouth, the more difficult it was. I was silently crying for my mom and dad. I’d miss them. I was full of shame for ruining everything.

I prayed, and frantically pleaded with Jesus to save me, to see me and hear me, including all the promises never to swear, never to talk back, never to steal any candy, never to secretly hate anyone; I promised to be a good girl, pleading through rolling tears, “Oh, please, Jesus, please please help me!”

And He did! It wouldn’t be the last time.

That killer snowball began to melt enough for me to dislodge the core of it from the back of my mouth, and finally chunks fell out relieving me of my anxiety and panic. I was soaked from head to toe with sweat, mucus, and spit. My hair was dripping wet with melted snow, my little fingers red and shaking, and my soft-skinned cheeks were chapped raw with winter’s bite, but I was alive!

I emerged in a state of euphoria from the limbs of my conifer. I was a warrior coming through the haze of residual gunsmoke, trudging proud, tear-stained, exhausted, and now, sure-footed. I had saved myself from certain death.

The snowball fight (and shoveling) was over, and we were being gathered up to go inside. The lawn was a mess, not an untouched pristine patch left. But my mother, who would be the first person to tell you life is ‘one disappointment after another,’ still had hope, knowing the snow was still falling and there would be a new layer by tomorrow.

Stripped, changed, safe and warm, I was to take my place at our vast kitchen table for a hot cup of Ovaltine, a malted chocolate drink popular in homes all over the Midwest in those days before Starbucks and Kuerigs, and specialty anything.

In the warm glow of the kitchen, surrounded by family, after a near-death experience that was just between me and God; I was particularly awake, observant, and grateful. My mom looked happy stirring and pouring hot Ovaltine into rarely used tall white mugs. My dad’s big hands, strong yet carefully passing out the mugs to little reaching fingers, with all the usual warnings to blow on it first, don’t spill, and that’s all you get! My sisters bragging about their athletic prowess and telling of the spoils of war, and there I was with my hands wrapped around those milk glass treasures, rosy-cheeked and radiant, I’m sure, but content to remain quiet and unnoticed in my rightful place as a little, middle child.

I was my own hero that night, lifting my mug of Ovaltine in cheers, for surviving a family snowball fight on a beautiful winter’s night somewhere back about 55 years ago. And though I may not have realized it then, it was just the first of many battles and accidents, and moments of fear and bravery that I would face in life.

Like snow upon snow, each new blanket covers up the scars of our private wars and mistakes, with the next perfect layer of hope, new possibilities, a sparkling new day to be grateful we’re alive, with a little extra effort so no one will slip and fall.

At the very least, I learned when to keep my mouth shut.

![p956070856-5[1]](https://clcurriedotcom.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/p956070856-51.jpg?w=300)